I always try to look ahead, not to think about my past.

But every time my parents say something, it comes back.

Again and again.

And it reminds me something about me, how it all started and how lucky I've been to get here.

When I was little, one day, they asked me to participate in a fencing tournament. A prestigious tournament, dedicated to the best talents of my age.

It cost 500 US dollars.

They were the equivalent of a month's salary of mom and dad combined.

They made enormous sacrifices to be able to bring them together.

In the end, I also won a prize, which consisted of the equivalent of 5 dollars, and then, completely unaware of the value of the money, I returned home triumphant, announcing to everyone that from now on, my saber would provide for the family .

That was not the case, of course.

I know these stories, but I don't really remember them.

I know them because my parents handed them down, they jealously guard them.

It’s their way of connecting the dots of our journey, of giving further depth to the present we are living.

A beautiful, full present. Happy.

The things that I remember instead, the ones that I really feel are mine, are much simpler, much more immediate.

I remember grandma's crepes.

She made them for me every morning, and they smelled great.

I remember that I was already a little boss in kindergarten, and that, growing up, the teachers and professors got angry at my ways of always getting what I wanted.

I was born and raised in Togliatti, a Russian city on the Volga, whose name is a clear tribute to the Italian statesman.

Until I was 14 we stayed there, and I remember all my school mates, and the ease I had in always being the first of the class. Effortless: everything came naturally to me, I always finished my homework in 5 minutes, and I succeeded in everything practically without studying.

It was my super power, which left me lots of free time for playing and fencing.

I had started with gymnastics, but the gym was far away, and it was too expensive for our family to take myself. Then my mother said that I could choose any other activity, as long as she met two conditions: that it was close to home, and that it was free.

So one day they asked me if I wanted to try fencing.

Fencing in Russian is fextovanie, which is a very difficult word for a child, and one I've never heard before. So, in my head, I had a completely different picture of what I would find in the gym.

I thought we would listen to music, or dance.

Things like that.

But when I entered the door of the Sport Hall I was overwhelmed by the sound of sabers and foils, and I immediately fell in love with that feeling of adrenaline and dynamism.

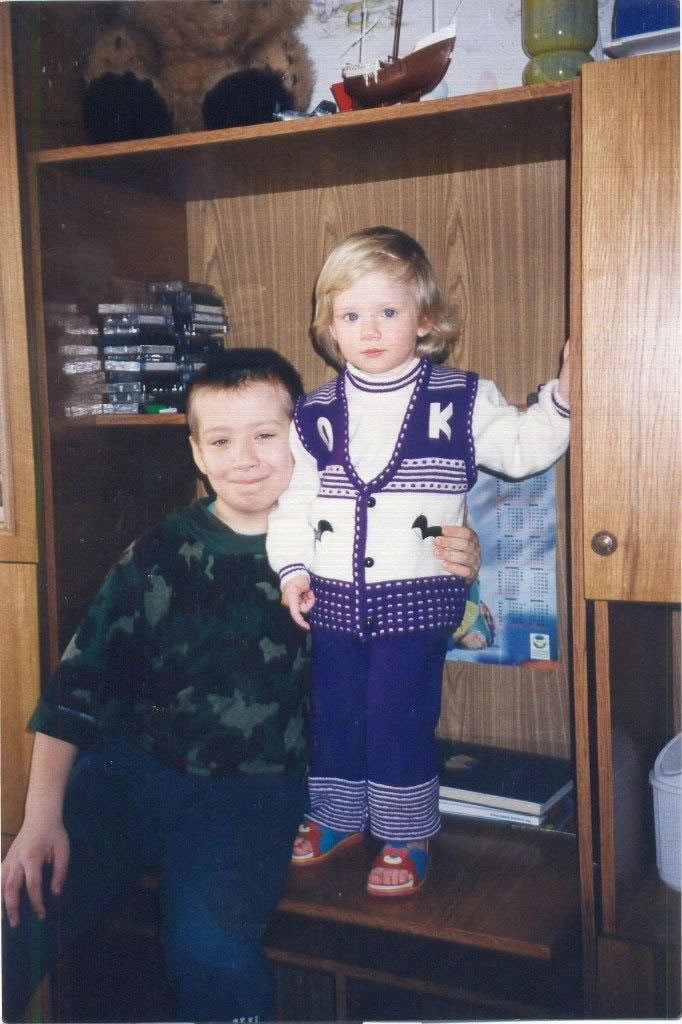

My brother, who was six years older than me, was already a huge fan, and he became something of a mentor, halfway between a coach and a fellow player.

“Every medal a cake.”

Every time I won a tournament, no matter the level, my parents would buy me a cake.

“Good business” I thought.

It seemed to me a very fair exchange, and absolutely advantageous for me. I found in that agreement an extra motivation to train with conviction.

Cake after cake, I became the best of the group.

Then the best of my club.

And when I finally realized that the better I got, the more I traveled, and the more I traveled, the less I had to go to school, I became the best in the city, in the region, and in all of Russia.

Maybe that's why even today, sometimes, I find it hard to see myself as a true professional, even if I am in all the aspects.

A part of me will continue to feel like a child forever, happy to be able to see the world for free, indeed even paid, to do something that perhaps, given how much she likes, she would do anyway.

It's a sport of emotion, where I always have to find something special to achieve, to fight for. My daily cake.

Even the simplest of workouts, if it's boring then I get sad, lose all fire and go out, like a lit match in a wind too strong.

And it's strange to say it now, that after the club, the city and the country, I've also become the best in the world, at least in theory. The number one in the world ranking.

Because this title touches me, and instead I don't want to think about it.

Sometimes I really don't know what to do with this information.

I don't know how I should feel.

I feel the pressure around me, I hear people greeting me saying “hello number one!” or “hello champ!”, and I would just like them to forget about it, leaving me free to simply be who I am.

The first place in the world ranking is only a small drop in the ocean, an achievement from which you can only regress. You're there, at the top, target for all the others, and there's nothing else you can do but try to always win.

As you would even if you were far from the top.

The difference is only in the weight of the defeat.

Then of course, I continue to be a dreamer.

A simple woman with complex desires.

First I wanted to go to the Tokyo Olympic Games.

Now I want to win those in Paris, and then I also want to win those in Los Angeles. When I have two Olympic gold medals I will be able to consider myself fulfilled.

But now, the number one next to my name, in addition to being a pride, is also a burden, a moral obligation to work double or triple to stay where I am.

And I've never liked working too much, much like studying.

I can even spend a whole day in the gym, sweating and practicing hard, as long as I don't feel like I'm working.

It happens very often: time flies by, between a trip and a tournament, an interview and a training session, and I still find it hard to believe that, at the end of the month, they pay me to do it.

It's my secret.

It's my fencing, my ambition, my happiness, lived one cake at a time, regardless of the consequences, and very attached to what's left for me.

For me as a woman, and for me as an athlete.

And perhaps this is really how sport should be experienced, by children and adults, by champions and beginners: much more than a job, but much less than a job.

As beautiful as the first day, and with glittering, dizzying prizes up for grabs.

Anna Bashta / Contributor